Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

Advertisement

Scientific Reports volume 14, Article number: 29771 (2024)

Metrics details

Deliveries performed by unskilled birth attendants is a concern in low-and middle-income countries such as Ethiopia. Unskilled birth attendants may lack the necessary medical knowledge and skills to handle potential complications during child birth. Hence, this study was aimed to assess spatial variation and associated factors of unskilled birth attendance in Ethiopia. This study used a total weighted sample of 7579 women who had a live birth in the five years preceding the survey obtained from EDHS 2016 data. ArcGIS 10.7 software was used to detect areas with a high prevalence of unskilled birth attendance in Ethiopia. Besides, a multilevel logistic regression analysis was done to identify associated factors of unskilled birth attendance. The spatial distribution analysis of unskilled birth attendants was significantly varied across the regions in the country with the significant hotspot areas in the eastern Somali, western Gambela, central and eastern Amhara, southwestern Oromia, eastern border of SNNP regions were detected. In the multilevel multivariable logistic regression model; women in age group (25–34), women attained primary and above educational level, women in the middle and richest household wealth status, mass media exposure, ANC visits, region, place of residence and health insurance coverage were significantly associated with unskilled birth attendance. The geospatial distribution of UBAs was varied across the regions of the country. Maternal age group, education level, rural residence, ANC visits, mass media exposure, wealth status, health insurance coverage and barriers in accessing healthcare service were determinant factors of unskilled birth attendance. Therefore, mothers who had no educational level, not covered by health insurance, women from poor households’ economic status, women from rural areas, and women who had no ANC visit should be given priority in terms of resource allocation including skilled personnel and access to healthcare facilities.

Unskilled birth attendants are defined as “those who assist a mother in childbirth and who initially acquired their experience through their own deliveries or through training with other traditional birth attendants1. It is well known that utilization of unskilled birth attendants during childbirth are associated with a high risk of maternal and neonatal morbidity, disability, and even death2. Unskilled birth attendance puts both the mother and the newborn at risk. The absence of proper medical knowledge and equipment can lead to complications during childbirth, such as hemorrhage, infections, and birth asphyxia. These complications often result in maternal and neonatal deaths that could have been prevented with skilled attendance and timely medical intervention3.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations’ (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have established a joint strategies that targets to reduce maternal mortality ratio to 70 deaths per 100,000 live births by 20304,5and this can be achieve through improving access to comprehensive maternal healthcare services and reduced the number of unskilled birth attendants6.

Worldwide, in 2020 maternal mortality rate was estimated to 223 deaths per 100,000 live births down from 227 in 2015 and it has been reduced by 34.3% over the last 20-years period. Despite this decrement, in 2020 approximately 800 women died every day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth7.

Although the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that skilled birth attendance should be present at every birth, whether the birth takes place in a facility or at home, each year millions of births still occur without any assistance from a skilled birth attendants8.

In Ethiopia maternal mortality rate is 412 per 100,000 live births, and the majority of maternal deaths are due to pregnancy and childbirth9. However, the implementation of some intervention to skilled deliveries the majority of childbirth in sab-Saharan Africa countries including Ethiopia are attained by unskilled birth attendants and continued to share the largest portion of global maternal, and newborn mortality10. Place of delivery is critical in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality, but in Ethiopia home birth by an unskilled birth attendant is very common11.

Despite the life-saving advantages of using skilled birth attendants (SBAs), a significant number of deliveries (16%) worldwide were performed by UBAs in between the years of 2015 to 2021. During this time period, the rate of UBA delivery was very high in South Asia (18%), in Sub-Saharan Africa (36%) and very low in Northern America and Europe (1%)8.

Home delivery with unskilled birth attendants after antenatal care service is a major contributing factor to the high MMR in SSA countries including Ethiopia. The spatial variations of unskilled birth delivery in SSA varies across countries ranging from 3% in South Africa to 69% in Chad12.

Most previous studies on the determinant factors of UBAs utilization at delivery in African countries showed that place of residence, HH’s wealth status, educational level of women, maternal age, desire for birth, occupation, media exposure, distance to a health facility, antenatal care visits and number of living children were identified as factors associated with unskilled birth attendant12,13,14,15. Overall, these studies show that mothers with the following characteristics are less likely to use UBAs: age group 35–49 year, secondary or higher educational status of mothers higher wealth status, exposure to mass media, urban residency, four or more ANC visits, knowledge of any family planning method, health insurance coverage, and having a short distance to a healthcare facilities.

Despite the commitments of extensive public health initiatives to skilled birth attendance, the majority of births in SSA are still performed by unskilled birth attendants, which continue to account for the greatest percentage of maternal and newborn mortality worldwide10.

The government of Ethiopia has made remarkable progress in improving maternal and child health outcomes, particularly through the expansion of skilled birth attendance. However, the presence home delivery with unskilled birth attendants remains a persistent barrier to safe and quality maternal healthcare16. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the spatial distribution and associated factors of unskilled birth attendance in Ethiopia. This study findings could help to give insights for policymakers, maternal health promoters, health practitioners in the country, to take targeted interventions for those regions with a high prevalence of UBA delivery.

The data for this study was obtained from the Ethiopian 2016 demographic and health survey (EDHS) which was conducted from January 18, 2016, to June 27, 2016. A two-stage stratified sampling method was used to sample units (clusters) consisting of enumeration areas (EAs). Administratively, Ethiopia is divided in to nine regions and two city administrations, and the regions are further divided into zones, and zones into units called woredas (districts), also district again subdivided into kebeles which is the lowest administrative unit. First, 645 enumeration areas (EAs) were selected using probability proportional to size (PPS). In the second stage, from each randomly selected EAs on average 28 households were selected by using systematic random sampling technique. Overall, a total of 18,008 households were selected and 16,583 women in the selected household were identified. The detailed sampling method has been described in the full report of EDHS 201617. For this study, a total weighted sample of 7589 women who had a live birth within five years preceding the survey were included.

Outcome variableThe outcome variable for this study was unskilled birth attendance which was constructed based on the categories used in EDHS. Deliveries assisted by traditional birth attendants (TBAs), traditional health volunteers, community/village health volunteers, relatives, and others were considered as unskilled birth attendance while all others were considered skilled birth attendance12,13,15.

Independent variables After reviewed related literatures fifteen independent variables both at individual and community-level were extracted.

The community-level variables place residence, region, barriers in accessing health care service and exposure to mass media were considered. The variables mass media exposure and barriers in accessing healthcare were not directly found in the EDHS data, and they were constructed their respective individual level factors. A woman was considered to have barrier in healthcare access, if a woman faced problems in permission, obtaining money, medical help or distance barriers and coded as “1” and if she faced no any barrier coded as “0”17,18,19. Also the community-level variable media exposure created as a women who had at least exposed to one media, either television, radio, or newspaper, and coded in a similar way. The other community-level variables (region and place of residence) were directly found in EDHS 2016 KR data file (Table 1).

The data was retrieved from the EDHS 2016, individual women records data set. The data recording, labeling and analysis were performed by using STATA/MP v-17. Descriptive summaries like crosstab were done to obtain the frequency and percentages for the independent variables. To identify significant predictors for the outcome variable; multilevel bivariable and multilevel multivariable binary logistic regression analysis were done. In the multilevel bivariable analysis, variables that were statistically significant at the p-value ≤ 0.2 were considered for a multilevel multivariable logistic regression model. A multi-collinearity test was run using the variance inflation factor (VIF) for all independent variables that significantly affected the outcome variable. The variance inflation factor (VIF) test revealed the absence of high multicollinearity between the variables (Mean VIF = 3.19).

Spatial distribution analysis of Unskilled Birth Attendance Weighted proportion of unskilled birth attendance delivery was mapped to illustrate the geospatial distribution. Spatial and hotspot analysis were conducted by using ArcGIS 10.7. The global spatial autocorrelation (Global Moran’s I) output ranges between (−1 to + 1). Values close to − 1 showed unskilled birth attendance delivery were dispersed and that close to + 1 indicated clustering. A statistically significant Moran’s I (P< 0.05) indicate spatial clustering of UBAs delivery and if the Global Moran’s I value is zero, UBAs delivery were distributed randomly20,21.

Hot spot (Getis-Ord Gi*) analysis To identify significant hotspot and cold spot areas of unskilled birth attendance delivery in the country, Getis-OrdGi * statistical hotspot analysis was done.

Spatial interpolationThe Kriging spatial interpolation technique was applied to predict the prevalence of UBAs delivered in un-sampled/unmeasured areas based on the values observed from sampled areas. There are distinct types of deterministic and geostatistical interpolation methods22. For this analysis, the Bayesian Kriging spatial interpolation method was used since it had a lower mean square error and residual.

As the nature of the data was hierarchical and, by assuming that women in the same cluster may had similar characteristics with women in another clusters in the country a two-level binary logistic regression model was used. Bi-variable multilevel analysis was done to identify candidate variables for multivariable multilevel analysis at a significant level of p-value less or equal to 0.25. Four models were constructed. First, a model with only outcome variable (null model) was fitted to assess the effect of communities (clusters) variation on unskilled birth attendance among women. The second model was random intercept model which had all its lower (individual-level) socio-demographic factors and assumes that these factors have fixed or constant association with unskilled birth attendance across clusters. The third model was fitted to look at the effects of community-level factors on unskilled birth attendants and assumed that the effects may vary across the clusters. Finally, the fourth model was fitted from both individual and community level variables simultaneously. Adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were computed for the variables.

Regarding the measures of variation (random effects) intra-cluster correlation coefficient (ICC), Proportional Change in Community Variance (PCV) and median odd ratio (MOR) were used. Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) quantifies the degree of heterogeneity of unskilled birth attendants between enumeration areas (clusters).

(ICC = frac{{sigma _{{U0}}^{2} }}{{sigma _{{U0}}^{2} + {raise0.7exhbox{${pi ^{2} }$} !mathord{left/ {vphantom {{pi ^{2} } 3}}right.kern-nulldelimiterspace} !lower0.7exhbox{$3$}}}}), where (sigma _{{u0}}^{2}) = between cluster (community) variance and (frac{{pi ^{2} }}{3}) = with in cluster (community) variance. The value of (frac{{pi ^{2} }}{3})in case of standard logistic distribution is 3.2923.

The median odd ratio (MOR) is quantifying the variation of unskilled birth attendants in between clusters and is defined as the median value of the odds ratio between the cluster at high risk of unskilled birth attendants and cluster at lower risk when randomly picking out two clusters (EAs).

(MOR = exp sqrt {(0.95*sigma _{{u0}}^{2} )}) Where (sigma _{{u0}}^{2})= between cluster (community) variance24.

PCV measures the total variation attributed to individual-level variables and community-level variables in the multilevel model as compared to the null model.

(PCV = left( {frac{{sigma _{{U0}}^{2} – sigma _{{u1}}^{1} }}{{sigma _{{U0}}^{2} }}} right)*100), Where (sigma _{{u0}}^{2}) = between cluster (community) variance in the null model and (sigma _{{u1}}^{2})is between community variance in the consecutive model25.

Furthermore, model comparison was also done based on Deviance (−2LL) and Akakian Information Criteria (AIC) test. The highest log-likelihood and the lowest AIC showed the best fitted model8.

For this study, a total weighted sample of 7,589 women who had a live birth in the five years preceding the survey were include. Based on the 2016 EDHS data, the overall national prevalence of unskilled birth attendance (UBA) was 66.93% with 95% CI (66.39, 69.12). The majority of women 3826 (50.42%) were between in the age group of 25–29 years. The percentage of women who used UBA at delivery in rural areas 4930 (74.46%) was much higher than that in urban areas 150 (15.49%). The majority of women 6579(91.5%) were married. About 3324 (46.2%) and 2369 (32.9%) were Muslim and Orthodox religion followers, respectively. Among those women 4791 (63.12%) had no formal education and 4078 (53.73%) of them had no occupation. A high proportion of women with have no educational level used UBA 3767 (78.64%). The highest proportion of unskilled birth attendance at delivery was found in Afar region 79.35% followed by Somali region 77.92% and the lowest in Addis Ababa 4.19% (Table 1).

A bi-variable multilevel binary logistic regression analysis, was conducted to have an insight into the association between UBA and determinant factors. Accordingly, Age groups, place of residence, maternal educational status, HHs wealth index, desire more children, health insurance coverage, knowledge of any family planning methods, number of ANC visit, media exposure, barriers in accessing healthcare service, place of residence and region were significantly association with UBA as the confidence interval don’t contain one (Table 2).

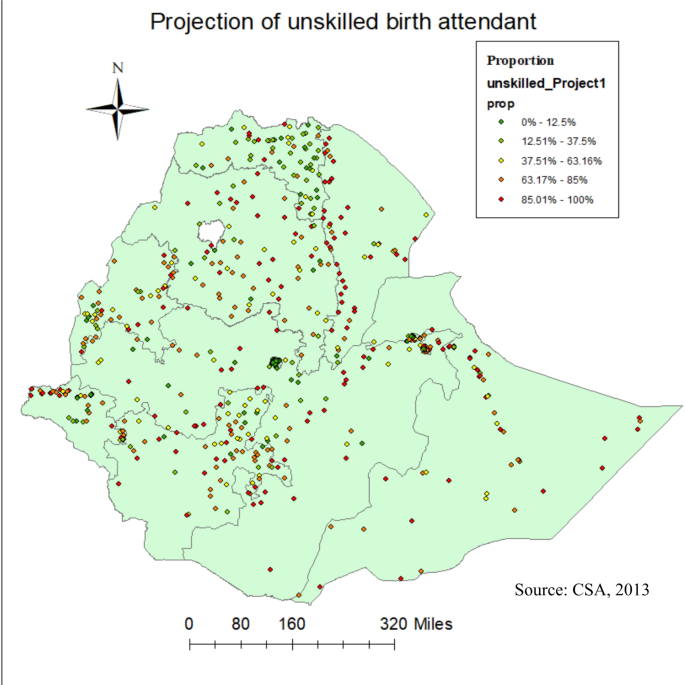

About 645 enumeration areas (clusters) were considered for spatial analysis of the unskilled birth attendance delivery. A higher prevalence of unskilled birth attendance deliver occurred in eastern Tigray, around the border between Amhara and Afar, northwest Amhara, south of Benshangule Gumuze, Northeast of SNNP, southwest of Oromia region, Dire-Dawa, Harari, and northern Gambela (Fig. 1).

Spatial distribution of prevalence of UBA delivery in Ethiopia using 2016 EDHS data.

The spatial distribution of UBA in Ethiopia has significantly clustered with significant Moran’s index across the country as the Global Moran’s I test value showed that 0.427 (p-value < 0.001) with a Z-score of 26.63 (Fig. 2). This shows that the spatial distribution of UBA in Ethiopia is non-random.

Spatial autocorrelation of unskilled birth attendance delivery in Ethiopia, EDHS 2016.

Hot spot analysis was conducted to detect the high-risk areas for UBA delivery in Ethiopia. The red dots color indicates that a higher proportion of UBA delivery and the blue dots color shows less risky areas for UBA delivery in Ethiopia. Figure 3 shown that southern parts of Afar, central and northeastern Amhara, eastern Somali, western Gambela, southwestern Oromia regions and northeastern SNNP regions have indicated more UBA delivery as compared to other parts of the country. However, the lowest UBA delivery was found in Eastern Tigray, Dire Dawa, Addis Ababa and Harari people’s regions which were indicated by blue colored dots (Fig. 3).

Hot spot analysis of unskilled birth attendance delivery in Ethiopia, EDHS 2016.

The Kriging interpolation identified southern Tigray, western and eastern Amhara, western Benshangule, southwest SNNPRs, and southeast Oromia regions as predicted to have high-risk areas of UBA delivery while the Addis Ababa, central Amhara, southern Oromia and southern Somali region were identified as predicted low prevalence of UBAs (Fig. 4).

Ordinary kriging spatial interpolation of UBA delivery in Ethiopia, 2016 EDHS.

Results random effect analysis and model comparison In the empty model (variance component analysis) the ICC value was 0.62 indicated that 62% total variation for unskilled birth attendance was due to the difference between clusters while the remaining 38% was explained by the between individual variation. The median OR in empty model (MOR = 9.13) indicated that, if we randomly select two women from two different clusters, women at the cluster with a higher risk of unskilled birth had 9.31times more likely of experiencing unskilled birth compared with women at cluster with a lower risk of unskilled birth. The PCV in the final model suggested that about 96% of cluster variability observed in the null model was explained by both community and individual-level variables.

Regarding model comparison, the final (mode-IV) was the best fitted-model since it had the highest likelihood, lowest deviance and BIC values (Table 2).

Results of fixed effects analysis In the combined model of multi-variable multilevel binary logistic regression analysis (model-IV) as it was the best fitted the data; the interpretation of fixed effects were based on this model. Consequently, respondent’s age group, maternal education status, households’ wealth status, ANC visit, knowledge of family planning methods, barriers in accessing healthcare service, region, place of residence, media exposure, and health insurance coverage were significantly associated with utilization of UBAs at delivery in the country.

The odds of USBs delivery among women aged 25–34 and 35–49 years were increased by 46% and 42% as compared to women in the age group 15–24 (AOR = 1.46, 95%CI = 1.22, 1.75) and (AOR = 1.42, 95%CI = 1.10, 1.83) respectively. Women whose educational level primary, secondary or above were less likely to utilize UBAs delivery compared with no educational status (AOR = 0.62, 95%CI = 0.53, 0.74), (AOR = 0.31, 95%CI = 0.22, 0.42) and (AOR = 0.14, 95%CI = 0.08, 0.25), respectively. Women with medium and rich household wealth index had the lowest odds of UBAs delivery compared to women with poor wealth index (AOR = 0.81; 95%CI = 0.66, 0.99) and (AOR = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.54, 0.81) respectively. Women from rural residents had 6 times more likely utilize UBAs at delivery as compared to the urban residents (AOR = 6.01; 95% CI = 4.33, 8.35). Mothers who had a mass-media exposure had 17% less likely utilized UBAs delivery (AOR = 0.83, 95%CI = 0.70, 0.98) compared to those with media exposure. Mothers who were covered by health insurance had a 37% less likelihood of utilizing unskilled birth attendant at delivery (AOR = 0.63, CI = 0.42, 0.94) compared to those covered by health insurance. Mothers who had four and above ANC visits had 87% less likelihood (AOR = 0.13, CI = 0.10, 0.16) of utilizing UBAs during delivery compared to women who had no antenatal care visits (Table 3).

This study aimed to assess the spatial variation and prevalence of UBA in relation to different socio-demographic factors among women in Ethiopia. Based on the 2016 EDHS data, the prevalence of unskilled birth attendants (UBA) in Ethiopia was 66.93% with 95% CI (65.86, 67.98). This study finding was higher than studies conducted in Chad 61.5%13, in Bangladesh 47.1%26and in Sub-Saharan African 44%12. The possible reason for this spatial variation might be due to women’s cultural attitudes and social beliefs differences across the countries.

The results of this study indicated that the geospatial distribution of UBA delivery had significant varied in the regions of Ethiopia. Significant hotspot areas of unskilled birth attendance delivery were detected in the boarder of Amhara and Afar regions, central and northeastern Amhara, southwestern Oromia region, eastern border of SNNP region, eastern Somali region and western Gambela region, whereas the safest regions were Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa, and central Tigray were identified as cold spot regions for UBAs delivery. This spatial variation might be the reason that lack of access to healthcare services, scarce resources such as skilled health professionals in, no mass media exposure and socio-cultural influence between women in different regions of Ethiopia27,28.

In the multilevel multivariable logistic regression analysis (Model-IV) age groups, maternal educational level, HHs wealth index, ANC visit, place of residence, region, health insurance coverage, and exposure to mass media were determinant factors of unskilled birth attendance at birth.

The odds of USB delivery among women aged 25–34 and 35–49 years were more likely than women in the age group 15–24. This result was supported by a study conducted in Ghana29and contradicts a study conducted in Nepal30. This variation might be due to the youngest women ignorance of unskilled birth attendants’ and the fear of complications during delivery.

In this study women who had primary and above educational levee were less likely to have unskilled attendance during delivery as compared to those who had no educational level. This finding is consistent with another studies conducted elsewhere31,32,33. The possible reasons for this could be; educated women are more aware of their health and seek to use modern health services like skilled health personnel birth assistance at delivery.

Women reside from rural areas had more likely to give birth by unskilled birth attendants than urban residence. This result is consistent with studies done in Bangladesh34, and Ethiopia35. This could be due to the fact that rural women do not have access to education about maternal health services. In addition, they may have difficulty in accessing health facilities, which may lead to very low utilization of prenatal care and a lower likelihood of SBA delivery36.

The findings of this study revealed that women from the richest and middle wealth status were less likely to use UBA during delivery than women with poor wealth status. This finding is consistent with studies conducted in rural Uganda37, in Kenya38, and in Bangladesh34. The possible justification, low wealth status may affect women’s ability to pay for transportation and other unexpected costs in the process of accessing health care service39.

This study also shown that, women who had antenatal care visits were less likelihood of utilizing UBA during delivery compared to women who had no antenatal care visits. This result was supported by studies conducted in Uganda37, in Zambia40and in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia41. The reason might be that women received health education and counseling about the risks of unskilled birth attendance during ANC visit.

In addition, this study revealed that women who had exposure to mass media were less likely to utilize the UBAs during delivery as compared to women who had no access to mass media. This result is in line with studies done in Northern Ghana42and in northern Ethiopia42. This might be due to the fact that mass media plays a prominent role in sharing essential information regarding maternal health care services.

Further, this study revealed that women who had covered by health insurance scheme had less likelihood utilizing UBAs during delivery as compared to who had no health insurance coverage. This result was supported studies conducted in India43, in Ghana44and in Kenya45. The possible reason might be health insurance coverage enables women to feel free to seek any medical care they need.

This study has strengths of using large data set and applied sampling weight to make it nationally representative to give reliable estimates and used multilevel analysis to account cluster correlations. Spatial distribution analysis were also done for identifying hotspot areas for interventions. However, the limitations of this study was a cross-sectional nature of the study design might be affects the cause-effect association, and finally the data might had a problems of recall bias such as a number of months for the birth interval.

This study examined that the spatial distribution of unskilled birth attendant was significantly varied across the region of country with the significant hotspot areas in the eastern Somali region, western Gambela region, central and eastern Amhara, in the boarder of Afar and Amhara regions, southwestern Oromia region, eastern border of SNNP region were detected. In the multilevel binary logistic regression analysis both individual and community-level variables were associated with unskilled birth attendance delivery. From Among individual-level variable, maternal age group, education level, ANC visits, wealth status, and health insurance coverage were significantly associated with unskilled birth attendance. In addition to this region, place of residence and community-level media exposure were among the community-level variables that had a statistical significant association with UBA delivery.

Therefore, areas with high prevalence of unskilled birth attendance, mothers who had no educational level, not covered by health insurance, women from poor households’ economic status, women from rural areas, and women who had no ANC visit should be given priority in terms of resource allocation including skilled personnel and access to healthcare facilities.

The datasets used during the current study is available from the corresponding author.

Akaike’s Information Criterion

Adjusted Odds Ratio

Enumeration Areas

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

Intraclass Correlation

Log likelihood Ratio

Median Odds Ratio

Proportional Change in Variance

Unskilled Birth Attendance

Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region

World Health Organization

Organization, W. H. Traditional Birth Attendants: A Joint (World Health Organization, 1992).

Khanna, D., Singh, J. V., Agarwal, M. & Kumar, V. Determinants of maternal deaths amongst mothers who suffered from post-partum haemorrhage: A community-based case control study. Int. J. Comm. Med. Public. Heal. 5 (7), 2814–2820 (2018).

Article Google Scholar

Olakunde, B. O. et al. Factors associated with skilled attendants at birth among married adolescent girls in Nigeria: Evidence from the multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, 2016/2017. Int. Health 11(6), 545–550 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Assembly G. Sustainable development goals. SDGs transform our world. 2030(10.1186) (2015).

Kuruvilla, S. et al. The global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health (2016–2030): A roadmap based on evidence and country experience. Bull. World Health Organ. 94(5), 398 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kawakatsu, Y. et al. Determinants of health facility utilization for childbirth in rural western Kenya: Cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14, 1–10 (2014).

Article Google Scholar

WHO U. UNFPA, World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division. Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2020: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF. UNFPA, World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division (World Health, 2023).

UNICEF. UNICEF. Delivery care [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Jun 5]. https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/delivery-care/ (2021).

Institute EPH. Federal Ministry of Health–FMoH, and ICF (EPHI/FMoH/ICF Addis Ababa, 2021).

Tessema, Z. T. & Tesema, G. A. Pooled prevalence and determinants of skilled birth attendant delivery in East Africa countries: A multilevel analysis of demographic and health surveys. Ital. J. Pediatr. 46(1), 1–11 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Abebe, F., Berhane, Y. & Girma, B. Factors associated with home delivery in Bahirdar, Ethiopia: A case control study. BMC Res. Notes 5, 1–6 (2012).

Article Google Scholar

Addo, I. Y., Acquah, E., Nyarko, S. H., Boateng, E. N. & Dickson, K. S. Factors associated with unskilled birth attendance among women in sub-saharan Africa: A multivariate-geospatial analysis of demographic and health surveys. PloS One. 18(2), e0280992 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Acquah, E. et al. Spatial and multilevel analysis of unskilled birth attendance in Chad. BMC Public. Health 22(1), 1561 (2022).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ogbo, F. A. et al. Prevalence, trends, and drivers of the utilization of unskilled birth attendants during democratic governance in Nigeria from 1999 to 2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17(1), 372 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bediako, V. B., Boateng, E. N., Owusu, B. A. & Dickson, K. S. Multilevel geospatial analysis of factors associated with unskilled birth attendance in Ghana. PloS One 16(6), e0253603 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kaba, M., Bulto, T., Tafesse, Z., Lingerh, W. & Ali, I. Sociocultural determinants of home delivery in Ethiopia: A qualitative study. Int. J. Women’s Health 93–102 (2016).

Csa, I. Central Statistical Agency (CSA)[Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey, Addis Ababa (Central Statistical Agency, 2016).

Bintabara, D., Nakamura, K. & Seino, K. Improving access to healthcare for women in Tanzania by addressing socioeconomic determinants and health insurance: A population-based cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 8(9), e023013 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tessema, Z. T. & Kebede, F. B. Factors Associated with Perceived Barriers of health Care Access Among reproductive-Age Women in Ethiopia: A Secondary Data Analysis of 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (NCBI, 2020).

Pfeiffer, D. U. et al. Spatial Analysis in Epidemiology (OUP Oxford, 2008).

Zulu, L. C., Kalipeni, E. & Johannes, E. Analyzing spatial clustering and the spatiotemporal nature and trends of HIV/AIDS prevalence using GIS: The case of Malawi, 1994–2010. BMC Infect. Dis. 14(1), 1–21 (2014).

Article Google Scholar

Bhunia, G. S., Shit, P. K. & Maiti, R. Comparison of GIS-based interpolation methods for spatial distribution of soil organic carbon (SOC). J. Saudi Soc. Agricultural Sci. 17(2), 114–126 (2018).

Google Scholar

Rodriguez, G. & Elo, I. Intra-class correlation in random-effects models for binary data. Stata J. 3(1), 32–46 (2003).

Article Google Scholar

Merlo, J. et al. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: Using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 60(4), 290–297 (2006).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Heck, R. H., Thomas, S. L. & Tabata, L. N. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling with IBM SPSS (Routledge, 2013).

Mahfuzur, M. R. et al. Exploring spatial variations in level and predictors of unskilled birth attendant delivery in Bangladesh using spatial analysis techniques: Findings from nationally representative survey data. PloS One 17(10), e0275951 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Teshale, A. B. et al. Exploring spatial variations and factors associated with skilled birth attendant delivery in Ethiopia: Geographically weighted regression and multilevel analysis. BMC Public. Health 20, 1–19 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Tessema, Z. T. & Tiruneh, S. A. Spatio-temporal distribution and associated factors of home delivery in Ethiopia. Further multilevel and spatial analysis of Ethiopian demographic and health surveys 2005–2016. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 20, 1–16 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Ameyaw, E. K., Tanle, A., Kissah-Korsah, K. & Amo-Adjei, J. Women’s health decision-making autonomy and skilled birth attendance in Ghana. Int. J. Reprod. Med. 2016 (2016).

Dhakal, S., Van Teijlingen, E., Raja, E. A. & Dhakal, K. B. Skilled care at birth among rural women in Nepal: Practice and challenges. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 29(4), 371 (2011).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fekadu, M. & Regassa, N. Skilled delivery care service utilization in Ethiopia: Analysis of rural-urban differentials based on national demographic and health survey (DHS) data. Afr. Health Sci. 14(4), 974–984 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bhowmik, J., Biswas, R. & Woldegiorgis, M. Antenatal care and skilled birth attendance in Bangladesh are influenced by female education and family affordability: BDHS 2014. Public. Health. 170, 113–121 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Abajobir, A. A. & Seme, A. Reproductive health knowledge and services utilization among rural adolescents in east Gojjam zone, Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 14(1), 1–11 (2014).

Article Google Scholar

Kibria, G. M. A. et al. Factors affecting deliveries attended by skilled birth attendants in Bangladesh. Maternal Health Neonatology Perinatol. 3(1), 1–9 (2017).

Article Google Scholar

Tadese, F. & Ali, A. Determinants of use of skilled birth attendance among mothers who gave birth in the past 12 months in Raya Alamata District, North East Ethiopia. Clin. Mother. Child. Health. 11, 164 (2014).

Google Scholar

Gabrysch, S. & Campbell, O. M. Still too far to walk: Literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 9, 1–18 (2009).

Article Google Scholar

Kwagala, B., Nankinga, O., Wandera, S. O., Ndugga, P. & Kabagenyi, A. Empowerment, intimate partner violence and skilled birth attendance among women in rural Uganda. Reproductive Health 13(1), 1–9 (2016).

Article Google Scholar

Nyongesa, C. et al. Factors influencing choice of skilled birth attendance at ANC: Evidence from the Kenya demographic health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18(1), 1–6 (2018).

Article Google Scholar

Ibrahim, H. A., Ajuwon, A. J. & Oladokun, A. Predictors of utilization of skilled birth attendants among women of reproductive age in Mandera East Sub County, Mandera County, Kenya. Sci. SPG J. Public Health 5(3), 230–239 (2017).

Article Google Scholar

Jacobs, C., Moshabela, M., Maswenyeho, S., Lambo, N. & Michelo, C. Predictors of antenatal care, skilled birth attendance, and postnatal care utilization among the remote and poorest rural communities of Zambia: A multilevel analysis. Front. Public. Health 5, 11 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lakew, Y., Tessema, F. & Hailu, C. Birth preparedness and its association with skilled birth attendance and postpartum checkups among mothers in Gibe Wereda, Hadiya Zone, South Ethiopia. J. Environ. Public Health 2016 (2016).

Saaka, M. & Akuamoah-Boateng, J. Prevalence and determinants of rural-urban utilization of skilled delivery services in Northern Ghana. Scientifica 2020 (2020).

Singh, M. K. & Ramotra, K. C. Skilled birth attendant (SBA) and home delivery in India: A geographical study. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 19(12), 81–88 (2014).

Article Google Scholar

Amoakoh-Coleman, M. et al. Predictors of skilled attendance at delivery among antenatal clinic attendants in Ghana: A cross-sectional study of population data. BMJ Open 5(5), e007810 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Were, L. P., Were, E., Wamai, R., Hogan, J. & Galarraga, O. The Association of Health Insurance with institutional delivery and access to skilled birth attendants: Evidence from the Kenya demographic and health survey 2008–09. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17(1), 1–10 (2017).

Article Google Scholar

Download references

We would like to thank the measure DHS program for providing us with all the relevant secondary data used in this study. Finally, we would like to thank all who directly or indirectly supported us.

We didn’t receive external funds for this research.

School of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Science, Dilla University, Dilla, Ethiopia

Gizaw Sisay Belay & Tsion Mulat Tebeje

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

GS and TMT conceived the study, involved in the study design, data analysis, drafted the manuscript and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Correspondence to Gizaw Sisay Belay.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Since we used secondary publicly available survey data from the MEASURE DHS program, ethical approval and participant consent were not necessary for this study. The approval letter for the use of the data set was also gained from the Measure DHS.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

Sisay Belay, G., Mulat Tebeje, T. Spatial distribution and determinants of unskilled birth attendance in Ethiopia: spatial and multilevel analysis. Sci Rep 14, 29771 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81484-x

Download citation

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81484-x

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Advertisement

© 2024 Springer Nature Limited

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.