Advertisement

BMC Public Health volume 24, Article number: 2788 (2024)

Metrics details

While the mental health benefits of urban green spaces (UGS) are increasingly recognized, less is known about how these relationships vary for socially marginalized groups. This study investigates the association between UGS and mental health among rural-to-urban migrants in Wuhan, China, examining the roles of the quality and quantity of UGS and the intermediary function of perceived everyday discrimination.

We used Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling to analyze data from a social survey, integrating with park-related social media ratings, street view imagery, and geospatial datasets to characterize UGS features and contextual factors, therefore verifying our hypotheses.

Both the quality and quantity of UGS significantly influence migrants’ mental health, with quantity demonstrating a stronger overall correlation, challenging common assumptions. Notably, social media scores of parks, reflecting positive user experiences, were found to improve mental health. However, the relationship with UGS quantity was nuanced: higher park density and green view index were positively associated with mental health, while increased park area proportion demonstrated the opposite effect. Furthermore, perceived discrimination emerged as a critical socio-psychological factor and operated spatial heterogeneity. In inner-city areas, neighborhoods characterized by plaza-type parks and high park density were associated with reduced perceived discrimination among migrants, showing active social functions of UGS. However, larger park areas are paradoxically correlated with increased discrimination experiences and poorer mental health. Interestingly, this mediatory effect of perceived discrimination was less pronounced in inner-suburban areas. These findings suggest a nuanced role of UGS in the lives of migrants. While certain aspects of UGS quantity, such as plentiful smaller parks, can facilitate social inclusion and improve mental health, others, like overlarge parks, may unintentionally contribute to feelings of marginalization and negatively impact mental health.

Our findings highlight the crucial need for context-sensitive green space planning that balances quality and quantity while mitigating discriminatory experiences to improve the mental health of rural-to-urban migrants.

Peer Review reports

Global rapid urbanization has caused severe health problems, including an increase in the prevalence of mental illness [1]. Industrial development has accelerated China’s land use transformation, leading to a loss in urban green spaces (UGS) and their uneven distribution, thus exacerbating the health disparities between rural migrants and local dwellers. In 2016, the State Council issued the Healthy China 2030 Planning Guidelines to address health concerns and highlight the importance of optimizing the greenspace system for health promotion. Critically, the plan underscores the goals of ‘One Health’, aimed at improving health across all social groups. It focuses specifically on rural migrants, who are at risk for mental illness due to social exclusion induced by spatial and cultural displacement for large-scale migration [2, 3]. Although previous research has thoroughly explored the health benefits of UGS in mainstream populations [4, 5], few studies have been conducted on rural migrants. The ‘migrants status’ as a factor in Social Determinants of Health (SDH) indicates not only differences in social structure but also potential inequalities in access to favorable facilities [6]. This paper focuses on rural migrants in urban China, an environmentally vulnerable group [3], and examines their exposure to neighborhood greenspace in terms of both quality and quantity, as well as the mental health outcomes associated with this exposure, aiming to enrich the body of research on environmental justice within urban green spaces.

Exposure to various attributes of greenspace has different implications for health outcomes. Scholars commonly examine their quality and quantity dimensions. The quality of UGS refers to elements that determine value and desirability, including aesthetic attractiveness, utility, and ecological diversity [7]. The quantity refers to the amount or extent of greenery in a specific geographical location, covering indoor or outdoor greenery, wild nature, pocket parks, wetlands, and other features [8]. The conventional methodology for evaluating the quality of UGS involves questionnaires and field audits [4]. Such methods are, however, subject to some drawbacks, such as subjective responses and participants’ recall bias, as well as being time-consuming and resource-intensive, which makes them challenging to implement on a large scale. To quantify the UGS, researchers frequently use geospatial data, satellite imagery, and other related datasets. Yet, these methods are constrained to an overhead perspective when measuring greenery, to some extent ignoring the eye-level. As urban computational science develops, an increasing number of studies utilize street-view images to capture the quality and quantity of UGS. Consequently, integrating multisource data is becoming a prevalent approach in environmental research. This study aims to contribute to urban environmental research by incorporating traditional survey data, geospatial information, and urban management data to explore the health effects of UGS through a nuanced, multifaceted lens.

Most previous research has concentrated on the UGS quantity, including street-view greenness, park density, and the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) [9,10,11,12]. Recent studies have examined quality factors such as naturalness, colorfulness, and cleanliness, but evidence in this area remains limited [13]. Four European cities demonstrated significant links between mental health and qualitative and quantitative greenness indices like garden design, tree count, and blue space size [14]. Research on new housing development projects revealed no correlation between park density and psychological distress, yet distress declined in areas with high-quality, well-maintained parks [15]. These inconclusive findings suggest that green space has varying effects on mental health, influenced by its quality and quantity.

In China, research on UGS is mainly directed towards mainstream groups, with limited attention given to rural migrants [16]. This oversight fails to address the unique challenges migrants face in accessing greenspaces due to their socioeconomic disadvantages and housing constraints. The hukou system, China’s distinctive household registration framework, has historically institutionalized the rural-urban societal divide, restricting internal mobility and creating differential access to resources [17]. Consequently, rural migrants are more susceptible to physical deprivation than their local counterparts [2], stemming from their disadvantaged position in the local housing market and lack of social and financial support [18]. This disparity extends to UGS access, as evidenced by studies in major Chinese cities. Research in Wuhan revealed a negative correlation (coefficient − 2.79) between UGS accessibility and the proportion of migrants in neighborhoods [19]. Similarly, in Guangzhou, over half of the neighborhoods exhibited unequal access to UGS for migrants [20]. These environmental inequalities can exacerbate spatial polarization, potentially intensifying disparities between migrants and local residents [21]. Such social consequences may further deteriorate migrants’ mental health [22].

On the other hand, rural migrants’ persistent housing mobility frequently results in the unstable usage of UGS [23], potentially impacting their mental health [3]. This instability not only limits their physical activity and civic engagement [24], but also results in fleeting encounters between migrants and local residents [25]. These transient interactions hinder the development of social connections between the two groups, potentially eroding social cohesion and increasing mental health issues [26]. Given the social inequalities in UGS access and the insufficient usage by migrants due to their mobile nature, the quantity of UGS may play a more critical role in promoting health among rural migrants compared to local residents. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

The quantity and quality of UGS significantly impact the mental health of rural migrants. Of these two factors, the quantity exerts a more pronounced effect.

While the social benefits of greenness are widely acknowledged [5, 27], their potential to exacerbate socio-spatial issues (such as perceived discrimination and deriving exclusion), particularly for migrants, requires careful consideration. High-quality UGS can attract people to stay longer and engage in a range of spontaneous activities (e.g., walking) and optional activities (e.g., recreation), as well as social interactions [15, 28]. Their health effects are determined by both their existence and the sociality it engenders [9, 15, 29]. Perceived discrimination, a formidable barrier to social integration, has sparked research interest in the social dynamics within UGS [5]. While studies from Ljubljana and Edinburgh suggested that suburban green spaces can reduce discrimination by encouraging citizen involvement [30], contrasting evidence reveals experiences of exclusion. For example, some Latino groups have reported feeling ‘out of place’, unwelcome, or marginalized when visiting parks [31].

As for China, housing market reforms have fueled socio-spatial stratification, exacerbating environmental injustice in urban areas [32], such as unequal access to UGS [33], which disproportionately impacts vulnerable groups such as migrants and low-income residents. Evidence from Beijing, Shenzhen, and Shanghai repeatedly confirms this pattern: while the priority commonly enjoys high-quality gardens in their private communities [21], underprivileged individuals frequently fail to access similar amenities [34, 35]. This disparity reinforces social polarization and perpetuates discrimination and exclusion through several spatial-social processes. A prime example is green privatization, often manifested in the proliferation of gated communities, which restricts public access to urban green spaces. This trend, often driven by market forces and neoliberal planning ideologies, results in a form of ‘green gentrification’ [36], where access to nature becomes a commodity reserved for the advantaged population. Physical barriers such as fences, walls, and strategically designed ‘soft’ landscaping elements serve to delineate social boundaries, control entry and exit of neighborhoods, and effectively limit opportunities for social interaction across socioeconomic/hukou-based lines [37]. This phenomenon is aptly illustrated in Wu et al.’s study of Beijing, which reveals how high-end gated communities create exclusionary enclaves with abundant green spaces, essentially privatizing what were once public amenities [21]. Beyond these physical barriers, hostile attitudes and discriminatory actions further restrict marginalized groups’ access to and enjoyment of green spaces. Activities perceived as disruptive and culturally discordant, associated with stigmatized status– such as square dancing in public parks–often provoke complaints and discriminatory responses [37, 38]. These microaggressions, though seemingly subtle, contribute to a negative social climate for disadvantaged groups, discouraging their use of green spaces and furthering existing social exclusion. In more extreme cases, the stark reality of discrimination lies through veiled ways, such as warning signs, small advertisements, and strategically placed posters that implicitly or explicitly target specific racial groups or outsiders [39]. While these methods may not always constitute overt legal violations, they nonetheless contribute to a non-inclusive environment. This covert form of discrimination often operates through coded language, imagery, or spatial practices that reinforce existing social hierarchies and marginalize targeted neighborhoods. Such practices highlight the urgent need to address not only the physical but also the social consequences of UGS inequality.

Even more problematic, the discrimination people experience in urban greenery isn’t localized; it impacts all walks of life [40, 41]. For migrants, this effect is more inescapable, as their status often magnifies the social disparities in accessing UGS [42]. This increased vulnerability is not limited geographically and can have long-term consequences for health, well-being, and social mobility. For example, a study in Dongguan, China, utilizing semi-structured interviews with temporary migrant workers, found that while squares near factories provided space for congregation, socialization, and exercise, interactions remained largely segregated, with rural fellows sharing similar migration backgrounds and reporting minimal interaction with local residents [41]. Although participants recognized the health benefits of using the square, they also mentioned ongoing discrimination experiences permeating their daily urban lives. This aligns with Zhang’s (2022) argument that green spaces may become sites of social division [43]. Despite shared physical presence, diverse groups’ avoidance behaviors in these spaces can reinforce segregation and marginalization of immigrant minorities, extending beyond the public realm. These findings suggest that discrimination experiences, whether specific to green spaces or reflecting broader everyday realities, may significantly impact migrants’ mental health. However, further research is needed to explore more diverse narratives among rural migrants in urban China. Accordingly, our hypothesis is:

UGS can indirectly affect the mental health of rural migrants through perceived everyday discrimination in urban China.

Further, the relationships between UGS, the social mediator, and mental health may hold differences across rural-urban contexts [5, 29, 44]. These differences, on the one hand, are attributed to the unequal distribution of UGS between suburban and central areas. Evidence from European cities suggested that compared to urban areas, around 77% of the population residing in the rural-urban interface lacks adequate access to UGS [45], which could bring about health issues. In England, despite abundant greenery in suburban and rural areas, it neither influenced health outcomes nor showed differences between these two areas [29]. Nevertheless, this conclusion is not universally applicable. In some cases, socially and economically disadvantaged populations may have access to more greenery in less privileged areas than their counterparts. Residents living in affordable housing and urban villages in urban China—considered underprivileged groups—have access to higher vegetation coverage rates than other urban populations [46]. These findings suggest that the health effects of UGS may be context-dependent along the rural-urban gradient.

On the other hand, their contextual heterogeneity may also result in differing social implications [22]. For instance, Neier (2023) identified segregation-based environmental inequality in Vienna [47], while in Beijing, lower-income areas have significantly reduced access to UGS, exacerbating spatial polarization between the rich and poor [21]. Scholars contend that this unequal distribution of ‘environmental goods’ like UGS is not coincidental but a consequence of long-term discriminatory policies [48]. The environmental marginalization of migrants was caused by a lack of recognition of their civic rights and informal livelihood strategies [49]. Additionally, their limited political capital often prompts governments and developers to pursue a ‘path of least resistance’, minimizing expenditure on environmental improvements at the expense of vulnerable groups [50]. The social effects of greenness, interlinked with rural-urban contexts, collectively influence one’s mental health.

This study, therefore, examines the impact of UGS on rural migrants’ perceived everyday discrimination and mental health outcomes. It further elucidates the heterogeneity of urban environments through comparative analyses of inner-city and inner-suburban areas. Building on the literature reviewed above, we propose:

The direct and indirect health impacts of UGS differ significantly between inner-city and inner-suburb, demonstrating the Geo-Contextualization of these effects.

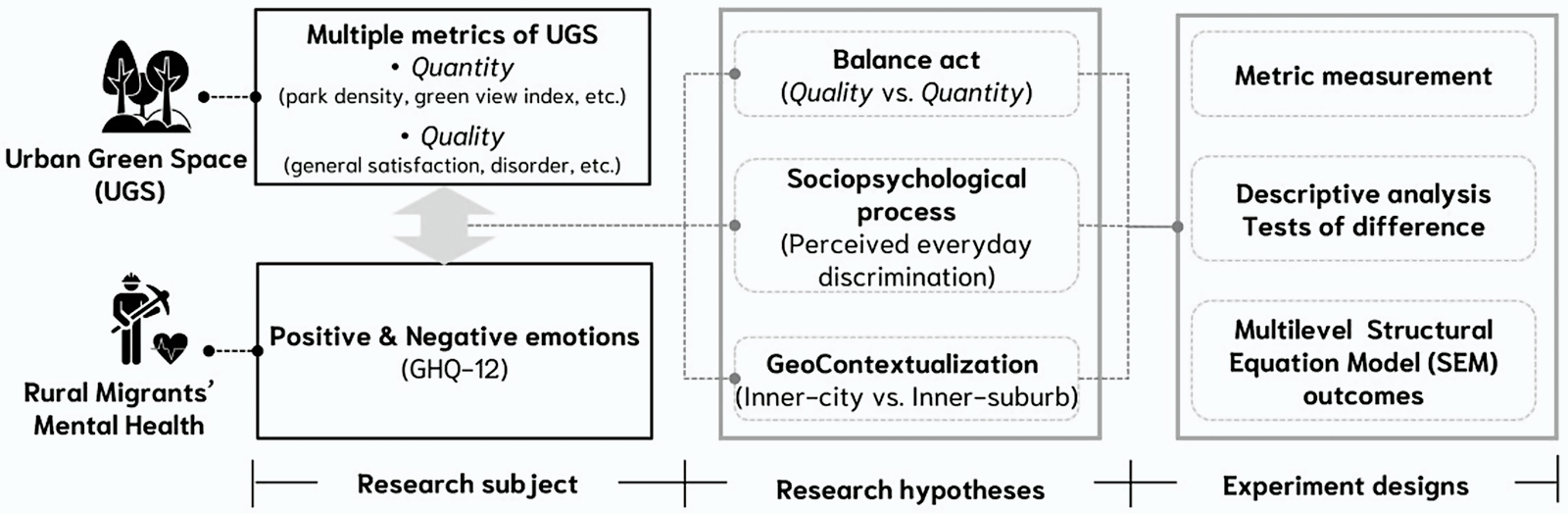

We validate the three hypotheses above by utilizing multisource data, incorporating the social survey, geospatial information, and urban environmental management data collected in Wuhan (see Fig. 1). Our findings underscore the necessity of inclusive planning, design, and management of UGS, advocating for a nuanced approach that accounts for the diverse attributes of greenness to which environmentally vulnerable groups are particularly sensitive.

Research design diagram

We chose Wuhan as the study area for three reasons. First, Wuhan is undergoing rapid urbanization, similar to Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, and it is one of the major migrant-receiving cities in China. According to the seventh national population census in 2020, the number of migrants in Wuhan reached 7.02 million, accounting for 32% of the total population, higher than the percentage (19.79%) in 2000 from the fifth national population census [51]. Second, there is a considerable geographical disparity in the residential environments of rural migrants in Wuhan. Statistics show that 35.4% resided in old inner areas, 28.7% in urban-rural fringes, and 16.6% in urban villages and squatter settlements [52]. This environmental heterogeneity underscores the importance of examining health issues across different ecological contexts. Third, following the COVID-19 outbreak, building a healthy city has been a leading strategy for Wuhan’s developmentFootnote 1. These features make Wuhan a typical case.

The spatial planning of Chinese cities follows a hierarchical structure: administrative districts, sub-districts (Jiedaos), and neighborhoods. Our primary data comes from the ‘Wuhan Neighborhood Environment and Migrants’ Quality of Life Survey’, conducted from September to November 2018. To sample participants, first, we selected ten Jiedaos from seven inner-city and three inner-suburb districts. Second, we implemented a street-interception, face-to-face survey for each selected Jiedao in specific neighborhoods. To ensure diverse representation among respondents, we administered the survey in the neighborhoods’ high-density areas frequented by a wide range of residents. These locations included entrances of grocery stores, convenience stores, supermarkets, parks, and areas adjacent to subway stations. Interviewers underwent specialized training to ensure consistent, unbiased respondent recruitment. The respondents were provided informed oral consent and received payment after the survey. The Ethics Committee of Wuhan University approved it. We cleaned the data by removing samples that completed the survey in an extremely short time or records with missing values, eventually obtaining 716 valid samples covering 60 neighborhoods. During the preliminary survey, we encountered several challenges specific to conducting door-to-door household surveys among migrant populations. These included the population’s high mobility, reluctance to participate due to defensive attitudes, incomplete registration information in neighborhood data, and our human and financial resources constraints. Consequently, we strategically adopted a street-intercept interview approach. To minimize selection bias, we carefully controlled age and gender balance during the survey, ensuring a sample that closely matched the demographics of the 2017 China Migrants Dynamic Survey (CMDS) (Table 1), strengthening the generalizability of our findings. The participants classified as rural migrants were selected based on the criteria that they were over 18 years old and had lived in Wuhan for at least six months without a Wuhan hukou, aligning with the definition of CMDS.

Apart from the survey data, we employed the following three datasets: (1) Parks’ social media rating data: we obtained it from the Dianping platform (https://www.dianping.com) tagged geo-location (one of the most informative life services and place rating websites in China) (LBSM)(August 2022); (2) Baidu Street view images (BSVs): we captured them from Baidu Maps (http://lbsyun.baidu.com/) (March 2021), the Chinese equivalent of Google Maps, which can offer diverse views and detailed information about the actual surroundings; (3) Neighborhood environment data: we obtained it from the Wuhan Land Resources and Planning Information Center (October 2020). This dataset covers information on land use, land surface vegetation cover, buildings, road networks, etc.

To address the 0–3 year lag between health and environmental data collection (2019.1–2022.12), we analyzed UGS changes, finding minimal landscape alteration (Fig. 2). While 28 new parks were added, none were within 800 m of sampled areas. Given this stability, and supported by existing research [8], we believe the time lag’s impact on health outcomes is negligible, maintaining the credibility of our conclusions for urban green space planning and public health policy.

Changes in UGS development within the sampled areas

Mental health was measured by the established Chinese version [53] of the General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12) [54]. Respondents rated the frequency of experiencing six positive (e.g., enjoying daily activities, feeling happy) (1 = never to 5 = always) and six negative (e.g., losing sleep due to anxiety, feeling nervous) emotions over the past 12 months. To minimize response bias, positive and negative items were clearly distinguished, and response scales were reversed for negative items (i.e., 5 = never to 1 = always). Moreover, to prevent individuals with severe mental illness from concealing or overestimating their mental health status, we emphasized the anonymity and confidentiality of responses throughout the survey. We calculated the final GHQ-12 score by summing all items, with higher scores indicating better mental health. This scale has demonstrated reliability in global public health research on migrant populations [3, 55, 56]. It has been instrumental in identifying individuals at risk of mental health difficulties and facilitating comparisons with other research.

Existing literature proposes various frameworks for measuring greenness exposure, including both overhead-view and eye-level perspectives [28], as well as subjective and objective dimensions [3]. Given the Chinese government’s policy focus and ongoing scholarly debate on the quality and quantity of UGS for vulnerable groups, this study evaluates rural migrants’ greenness exposure along these two critical dimensions.

This study centered on four common aspects of the quality of UGS [9, 57]: overall satisfaction, social media ratings, greenspace disorder, and the presence of recreational plaza-type parks. Specifically, the overall satisfaction with UGS was measured by a 5-point Likert scale (1 = extremely dissatisfied to 5 = totally satisfied) based on the question, ‘How satisfied are you with the quality of greenspace in your neighborhood?’. Additionally, to capture public perceptions of park quality, we incorporated user-generated social media ratings from the Dianping website. This platform features anonymous reviews of parks, incorporating aspects like cost, aesthetics, and activity offerings. We calculated a weighted average rating for each neighborhood based on the five nearest parks, employing an inverse distance weighting method, as showed in Equation. A1, Appendix. Parks were weighted at 0.4, 0.3, 0.1, 0.1, and 0.1 [58], respectively, according to their proximity (calculated using road network distances) to the neighborhood centroid. The farthest park analyzed was within a 4.17 km radius, accessible within 30–60 min by public transportation [59]. This accessibility criterion ensured all parks were reachable within a reasonable timeframe, justifying our decision to set the weight of the fifth park to 0.1 instead of 0. Drawing upon established audit tools [9, 57], we quantified greenspace disorder using data on environmental enforcement actions related to UGS management. This dataset, provided by the Wuhan City Urban Management and Law Enforcement Commission, documented instances of littering, solid waste accumulation, and maintenance issues (e.g., bare vegetation, inadequate facilities, or lighting) in UGS within an 800 m radius of each neighborhood. A higher density of reported cases signifies greater disorder within the UGS. Recreational plaza-type parks were identified as a crucial indicator of UGS quality. Park boundaries were extracted from remote sensing imagery, the Gaode Map platform, and the Wuhan City Park Directory (see Fig. A1, Appendix). We classified parks based on the ‘Urban Green Area Classification Standard CJJ/T 85-2017’Footnote 2 released by China’s Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development. This variable was operationalized as a binary indicator (1 = presence, 0 = absence).

To measure the quantity of UGS, we employed three widely used metrics [9,10,11,12]: park density, park area ratio, and the Green View Index (GVI). These measures allow for meaningful comparisons with other studies and contexts. We calculated park density as the number of parks within an 800 m radius buffer around each neighborhood centroid. Park locations were extracted from points of interest (POIs) accessed through the Baidu Map API. The park area ratio, calculated as the proportion of land dedicated to parks, was derived using GIS data on land use classification obtained from the Wuhan Land Resources and Planning Information Center. To quantify the visibility of greenery, we computed the GVI using Baidu Street View imagery [10]. Data collection points were established at 100-meter intervals along the road network within the 800 m buffer. At each point, we captured panoramic street-level images (500 × 500 pixels) in four cardinal directions (90°, 180°, 270°, 360°) using a Python script. We then employed a fully convolutional neural network (FCN-8s) for semantic segmentation, enabling the identification and extraction of green elements (e.g., trees, grass) within each image [10]. The GVI at each point was computed as the average proportion of green pixels across the four directional images. The neighborhood-level GVI was then determined by averaging the GVIs of all collection points within the corresponding buffer zone.

Prior research has employed diverse definitions of ‘neighborhood,’ including Transportation Analysis Zones (TAZs), zip codes, census tracts, blocks, Jiedaos, and radial buffers ranging from 100 m to 2 km. Given the focus of this study on creating health-oriented neighborhoods, we defined ‘neighborhood’ using an 800 m radius buffer. This decision aligns with Wuhan’s ‘Planning Action for 15-Minute Community Life Circle’ (2018), which designates a 500–800 m radius as the primary daily living space based on a 15-minute walking distance. This operationalization enhances the practical implications of our findings for urban planning and public health initiatives.

We measured perceived everyday discrimination (PED) by adapting the Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS) [60]. This adapted scale, reflecting prevalent discrimination issues reported by Chinese migrants, comprises three items quantifying respondents’ experiences of being disliked, treated with contempt, and facing reluctance from the local population as neighbors. Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), with higher summed scores indicating greater perceived discrimination. While this measure captures general daily discrimination rather than being green space-specific, we argue for its ecological validity as our study is situated within a broader investigation of neighborhood environments and migrant quality of life in Wuhan. Discrimination experienced by migrants permeates various aspects of daily life [40], including but not limited to UGS interactions operating within a broader social and spatial context. Literature also suggests that UGS-related discrimination often extends beyond geographical boundaries [2]. Examining everyday discrimination provides a more comprehensive lens for understanding environmental injustice experienced by migrants in urban settings.

We included a set of individual characteristics as control variables [3,4,5, 28], such as age, gender, and educational status (Table 1). Personal annual income was also considered a dichotomy based on Wuhan’s per capita yearly income 2019Footnote 3. A value of 1 (High) was assigned to the income above the average (≥ 50,000 CNY), while a value of 0 (Low) was given to the income below the average (<50,000 CNY). We grouped the residential location into inner-city (0) and inner-suburb (1).

Our data analysis comprised three main steps. First, we performed descriptive analyses using Chi-square and t-tests to examine statistical differences in UGS, perceived everyday discrimination, and mental health across rural-urban contexts. Second, to address the hierarchical nature of our data (individuals nested within neighborhoods), we aggregated environmental data captured by each individual response to the neighborhood level. This aggregation was done by calculating the mean score for each environmental variable within each unique neighborhood identifier, effectively transitioning from individual-level to neighborhood-level data. Third, we applied Multilevel Structural Equation Models (MSEM) to test our hypotheses by examining the relationships between greenness exposure, the mediator, and mental health outcomes among rural migrants. We estimated the significance of each pathway, indirect effects, and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Multiple models were conducted to compute direct, indirect, and total effects within each pathway, considering different residential locations to understand their varying impacts in rural-urban contexts. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for all variables averaged 1.4 (below the threshold of 5), suggesting the absence of severe multicollinearity. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 16 [61], employing commands such as ‘ttest’, ‘gsem’, and ‘nlcom’.

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics. The average score of the GHQ-12 was 46.42 (SD ± 5.03), close to the health score’s median value. 15.82% of the respondents reported having ‘always’ and ‘often’ lost much sleep due to over-anxiety and ‘feelings of nervousness,’ indicating that rural migrants in Wuhan generally experienced unsatisfactory mental health and some emotional distress. Additionally, groups residing in the inner-city exhibited more favorable mental health.

For the UGS quality, the average score of the general satisfaction and parks’ social media rating was 3.45 (SD ± 0.49) and 4.33 (SD ± 0.35), respectively. The average number of environmental management cases reported by residents was 2.86; over half of the neighborhoods (56.70%) had urban management problems with greening (with values exceeding 1). Only 30.59% had recreational plaza-type parks. For the quantity, the park density, park area ratio, and GVI averaged at 1.10 (SD ± 1.45), 0.09 (SD ± 0.16), and 0.28 (SD ± 0.07), respectively.

Table 2 illustrates the disparities in UGS characteristics across rural-urban contexts. Inner-city neighborhoods, where migrant workers reside, exhibited higher park density (by 1.12 units) and park area ratio (by 0.06) compared to inner-suburban areas. Conversely, the inner-suburb demonstrated a significantly higher green view index (by 0.05 units). Qualitatively, inner-city respondents reported greater perceived greenery satisfaction (by 0.38) and higher park social media ratings (by 0.23). However, these areas also faced more greenspace disorder issues, with environmental management cases exceeding those in inner-suburban areas by 1.01. Inner-suburban areas, in contrast, featured a higher proportion of recreational plaza-type parks. These findings reveal unequal access to UGS among migrant populations across the rural-urban continuum.

Additionally, rural migrants experience a moderate everyday discrimination from local residents, with an average score of 6.40 (SD ± 1.90) out of 15. While the difference isn’t statistically significant, the data indicates a potential trend where migrants in inner-suburban areas may face slightly higher levels of discrimination than those in inner-city areas. This marginal difference of 0.21 could be explored further in future research to determine its significance and potential underlying factors.

We ran the model of the direct health effects of UGS, accounting for covariates. Subsequently, the model was re-estimated to include the discrimination factor as a mediator. Model fit was evaluated by comparing the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) across the two models [62], with lower values indicating better model fit. As shown in Table 3, across both the overall sample and the subsamples categorized by residential location, models incorporating perceived discrimination (Models 2, 4, 6) exhibited lower AIC and BIC values compared to those without (Models 1, 3, 5), suggesting its potential role as a social mediator in these associations.

Table 4 presents the detailed modeling results, illustrating the direct, indirect, and total effects. As hypothesized (H1) and evidenced by the model, the quantity of UGS demonstrates a more decisive influence on the mental health of rural migrants in Wuhan compared to quality aspects, partially contradicting previous studies on the general population [14, 15]. However, these effects differ significantly between inner-city and inner-suburban areas (Tables A1 and A2, see Appendix), highlighting the importance of considering the quality and quantity of UGS concerning the Geo-Contextualization of health effects.

Specifically, high park density was significantly and positively correlated with mental health among rural migrants overall (βdirect = 1.119, p < 0.05), with a stronger effect in the inner-city area (βdirect = 1.412, p < 0.01, Appendix, Table A1). Additionally, each percentage point increase in GVI was associated with a 8.45-point rise in mental health scores, a benefit particularly evident in suburban areas. However, the relationship between quantity and mental health is not always straightforward. Unexpectedly, a larger park area ratio is associated with poorer mental health (βdirect = -3.611, p < 0.1), especially for inner-suburban migrants (βdirect = -7.568, p < 0.05, Appendix, Table A2). This finding challenges previous studies [4, 7] and suggests that simply increasing park size may not necessarily translate into better health, particularly in areas already abundant in greenness.

Despite the dominant influence of quantity, qualitative aspects of UGS also demonstrate significant, albeit context-dependent, associations with mental health. Social media ratings of parks show a significant, positive association with mental health (βdirect = 2.142, p < 0.01), but only in inner-suburban neighborhoods (βdirect = 6.019, p-value = 0.015, Appendix, Table A2). This finding suggests that living near highly-rated parks, especially those praised for their scenery, aesthetics, and overall attractiveness, may significantly improve mental health for inner-suburban migrants. Interestingly, perceived greenery satisfaction holds a nanced relationship. While generally positive, this relationship becomes significantly negative within the inner-city (βdirect= -1.137, p-value = 0.056). This could be attributed to the confounding influence of housing market dynamics, where high greenspace satisfaction often coincides with elevated property values, potentially offsetting the mental health benefits [63]. Furthermore, the mental health benefits of recreational plaza-type parks appear to be context-dependent, specifically benefiting inner-city migrants (βdirect = 0.996, p < 0.1) while not showing the same effect, and potentially even a slightly negative (although statistically insignificant) one, for inner-suburban migrants (βdirect= -1.253, p > 0.1).

Furthermore, our findings confirm H2 and H3 about the role of perceived everyday discrimination in the relationship between UGS and mental health, and reveal critical differences between urban and suburban areas. In suburban areas, urban greenery more directly benefits mental health. However, in inner-city areas, the experience of discrimination plays a crucial mediating role. Specifically, for inner-city migrants, living near parks with recreational plazas is linked to better mental health, partly because it reduces experiences of discrimination (βindirect = 0.332, 95% CI: 0.060 to 0.605, Appendix Table A1). This contrasts sharply with rural migrants, especially those in inner-suburban areas, who showed a strong negative correlation between perceived discrimination and mental health (Fig. 3). While some trends suggested that greenspaces with favorable social media ratings (suburban) and satisfaction (inner-city) might also reduce discriminatory experiences (Fig. 3), these did not reach statistical significance. Therefore, while access to high-quality UGS may lessen the negative mental health impacts of discrimination, particularly for inner-city migrants, this effect is not consistently observed across all rural-urban settings.

While UGS quality generally produces the positive social outcomes, the relationship between their quantity and social dynamics is more nuanced. The social functions of UGS, such as reducing discrimination, appear to reverse under certain quantitative conditions. A high proportion of greenness, particularly in the inner-city (βindirect = -0.965, 95% CI: -1.843 to -0.087, Appendix Table A1), was associated with increased perceived discrimination and consequently poorer mental health. This phenomenon may be attributed to these areas primarily serving as city-level parks [59], where proximate neighborhoods have experienced social segregation related to household registration or income, thereby amplifying discrimination and adversely impacting rural migrants’ mental health. Conversely, higher park density was linked to lower perceived discrimination and improved mental health (βindirect = 0.078, 95% CI: -0.084 to 0.239, Table 4), suggesting that accessible UGS can facilitate social integration.

Ultimately, this study highlights the health influence of both quantitative and qualitative dimensions of UGS and differs across specific urban-rural contexts. In inner-suburban areas, proximity to moderately sized parks but high social media ratings and visibility significantly contributes to positive mental health outcomes for migrants. Conversely, in inner-city areas, high park density and recreational plaza-type parks prove more beneficial. Perceived discrimination emerges as a critical psychosocial mechanism. Neighborhood parks designed as recreational squares can indirectly promote mental health by mitigating perceived discrimination. However, a high proportion of UGS in an area may inadvertently exacerbate social segregation, negatively impacting mental health. These findings emphasize that the effective green spaces planning must consider their both quality and quantity across different urban zones to maximize health benefits for rural migrants.

Significant pathways across rural-urban contexts. *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01

Under the ‘mobility turn’ in environmental health studies, the importance of neighborhood greenness exposure for rural migrants’ mental health has received growing attention. Taking Wuhan as a typical case, our study reveals that both the quantity and quality of UGS significantly impact migrants’ mental health, with quantity demonstrating a stronger correlation. This contrasts with findings from low-density cities, such as those in the Netherlands [9] and Australia [15], where the quality has been strongly influenced. The inconclusive results can be attributed to the city-specific urban form and the progress made in greening. The high-density built environment, fragmented spatial layout resulting from the presence of rivers and lakes, and transportation challenges inherent to Wuhan exemplify how these factors can exacerbate unequal access to UGS. These findings underscore the urgency for Wuhan to prioritize equitable green space development.

A focus on detailed information revealed that only the social media ratings of parks exerted a positive influence. Unexpectedly, a higher proportion of park area was linked to poorer mental health. This finding corroborates extant literature suggesting a non-linear correlation between UGS and psychological well-being, aligning with the hypothesized ‘Greenery Saturation Effect’. The theory suggests that surpassing an optimal UGS exposure threshold may elicit adverse emotional responses [64]. Various studies provide evidence for this effect. For instance, Australian children’s happiness peaked with 21–40% green space coverage [65], while older adults’ overall health was optimal at an NDVI of 0.4 [66]. Exceeding these levels may yield diminishing returns or even detrimental effects on mental health. Several factors could explain this counterintuitive relationship. Larger parks often struggle with adequate security and lighting, potentially increasing crime risk and residents’ fear and stress [67]. For migrants in particular, extensive parklands may paradoxically restrict their opportunities for interaction with local residents, thus contributing to social isolation and negatively impacting mental health. Moreover, as illustrated by our fieldwork (Fig. 4), prioritizing UGS for vulnerable groups concentrated in urban villages and affordable housing can strain municipal budgets. This financial burden often results in inadequate maintenance, reduced amenities, and diminished UGS quality, thereby undermining the intended health benefits. In conclusion, while green spaces generally support mental health, their effectiveness depends on factors beyond mere quantity, including quality and social considerations.

Observations of UGS conditions in migrant settlements (July 2021) By author. Note urban villages in the inner-city (Left) and affordable housing neighborhoods in the inner-suburb (Right)

We also observe the health effects of UGS differing along the rural-urban gradient. In inner-city areas, a higher density of parks directly promotes migrants’ mental health. Conversely, in suburban areas, the quality of parks, as indicated by social media ratings, has a more significant positive impact. This disparity can be attributed to Wuhan’s uneven distribution of ecological resources, particularly its circular arrangement of larger, more ecological suburban parks, contributes to this disparityFootnote 4. While expansive, these parks face management and social functionality challenges. Our findings reveal a negative correlation between suburban migrants’ mental health and park area proportion, potentially due to increased exposure to fragmented greenness. Limited mobility in transit deserts may further exacerbate this issue [68]. These differing inner-city and suburban outcomes highlight divergent social processes. Inner-city green spaces can mitigate the mental health impacts of daily discrimination, an effect absent in suburban settings. This discrepancy likely stems from two interconnected factors related to Wuhan’s suburban environment: its rural-like nature, which can exacerbate migrants’ social withdrawal [41], and its highly segregated socio-spatial structure [69]. Both contribute to migrants interacting almost exclusively within their own identity group, thus impairing their sense of place and belonging. Consequently, suburban green spaces, despite their potential, minimally buffer the mental health impacts of discrimination among migrants compared to inner-city counterparts.

This study offers threefold contributions to the understanding of the health effects of UGS on the migrant population: (1) Geo-Contextualization of health effects: We demonstrate that the mental health outcomes of rural-to-urban migrants in urban China are significantly influenced by their residential location (inner-city vs. inner-suburb), highlighting the context-dependent nature of individual outcomes. (2) Nuanced green space impacts: While affirming the general health benefits of UGS for rural migrants, an overabundance of greenery, particularly in suburban areas, can be detrimental. Urban planning must balance UGS quality and quantity. (3) Contextual moderation of discrimination: We uncover spatially heterogeneous effects, with social mechanisms, such as reduced perceived everyday discrimination, driving the health benefits of UGS in inner-city areas. Conversely, in inner-suburban areas, these benefits manifest more directly, reflecting the influence of localized landscape characteristics and population distribution. This research builds upon and refines existing studies on the diverse health impacts of UGS across rural-urban gradients, emphasizing the need for context-specific urban planning interventions.

Despite the study’s contributions, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, while widely used, self-reported measures like the GHQ-12 are susceptible to response bias. Future research would benefit from incorporating additional mental health instruments, such as the GAD-7 and PSS, for cross-validation and exploring migrant-specific mental health concerns. Secondly, although socioeconomic variables were controlled for, the potential impact of mobility experience on rural migrants’ mental health warrants further investigation. Finally, due to data limitations restricting analysis to UGS presence, this study may underestimate migrants’ frequency and duration of UGS use. Future studies should collect detailed usage information to better understand its relationship with mental health, considering both availability and actual utilization.

These findings have several policy implications for developing healthy and inclusive cities. Firstly, while increasing urban green space is generally beneficial, a nuanced approach to balancing quantity with strategic quality enhancements is crucial. Policies should prioritize optimizing park density, visibility, and social value to cultivate positive public perception, particularly for environmentally disadvantaged populations. Secondly, designing inclusive and social green spaces is essential to mitigate potential discriminatory practices. This involves prioritizing human-scale designs that promote interaction and discourage territorial behavior. Additionally, government and community-led programming can foster social cohesion and intercultural exchange, cultivating a sense of belonging among migrants. Lastly, embracing context-specific design is vital. Inner-city interventions should focus on increasing park density through pocket parks and recreational plazas, while suburban strategies should enhance the social functionality of existing green spaces through improved amenities and engaging activities. By tailoring green space design to specific user groups and settings, cities can maximize the positive impact of these spaces on community well-being and social integration.

The data is not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author(chenghanbei@swjtu.edu.cn).

More information could be found at URL: https://www.wuhan.gov.cn/zwgk/xxgk/zfwj/szfwj/202203/t20220331_1948391.shtml.

More information can be found at https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/gongkai/zhengce/zhengcefilelib/201806/20180626_236545.html.

More information can be found at https://tjj.wuhan.gov.cn/tjfw/tjfx/202004/t20200429_1189624.shtml.

More information can be found at Bulletin Of Wuhan Greening Situation In 2022, URL: http://ylj.wuhan.gov.cn/zwgk/zwxxgkzl_12298/tjxx/lhgb_12361/202303/t20230314_2169414.shtml.

Urban Green Spaces

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index

China Migrants Dynamic Survey

Greenness Exposure

Mental Health

Park Density (log)

Park Area Ratio

Green View Index

General Satisfaction

Parks’ Social Media Rating

Greenspace Disorder (log)

Recreational Plaza-type Parks

Perceived Everyday Discrimination

Pelgrims I, Devleesschauwer B, Guyot M, Keune H, Nawrot TS, Remmen R, et al. Association between urban environment and mental health in Brussels, Belgium. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:635.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Li J, Rose N. Urban social exclusion and mental health of China’s rural-urban migrants: a review and call for research. Health Place. 2017;48:20–30.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Yang M, Dijst M, Faber J, Helbich M. Using structural equation modeling to examine pathways between perceived residential green space and mental health among internal migrants in China. Environ Res. 2020;183:109121.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dzhambov AM, Markevych I, Hartig T, Tilov B, Arabadzhiev Z, Stoyanov D, et al. Multiple pathways link urban green- and bluespace to mental health in young adults. Environ Res. 2018;166:223–33.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lachowycz K, Jones AP. Towards a better understanding of the relationship between greenspace and health: development of a theoretical framework. Landsc Urban Plann. 2013;118:62–9.

Article Google Scholar

Fleischman Y, Willen SS, Davidovitch N, Mor Z. Migration as a social determinant of health for irregular migrants: Israel as case study. Soc Sci Med. 2015;147:89–97.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Shuvo FK, Feng X, Akaraci S, Astell-Burt T. Urban green space and health in low and middle-income countries: a critical review. Volume 52. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening; 2020. p. 126662.

Wang R, Feng Z, Pearce J, Liu Y, Dong G. Are greenspace quantity and quality associated with mental health through different mechanisms in Guangzhou, China: a comparison study using street view data. Environ Pollut. 2021;290:117976.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

De Vries S, Van Dillen SM, Groenewegen PP, Spreeuwenberg P. Streetscape greenery and health: stress, social cohesion and physical activity as mediators. Soc Sci Med. 2013;94:26–33.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Helbich M, Yao Y, Liu Y, Zhang J, Liu P, Wang R. Using deep learning to examine street view green and blue spaces and their associations with geriatric depression in Beijing, China. Environ Int. 2019;126:107–17.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Houlden V, Weich S, Jarvis S. A cross-sectional analysis of green space prevalence and mental wellbeing in England. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:460.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wu Y-T, Nash P, Barnes LE, Minett T, Matthews FE, Jones A, et al. Assessing environmental features related to mental health: a reliability study of visual streetscape images. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1094.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ahn JJ, Kim Y, Lucio J, Corley EA, Bentley M. Green spaces and heterogeneous social groups in the US. Volume 49. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening; 2020. p. 126637.

Ruijsbroek A, Mohnen SM, Droomers M, Kruize H, Gidlow C, Gražulevičiene R, et al. Neighbourhood green space, social environment and mental health: an examination in four European cities. Int J Public Health. 2017;62:657–67.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Francis J, Wood LJ, Knuiman M, Giles-Corti B. Quality or quantity? Exploring the relationship between Public Open Space attributes and mental health in Perth, Western Australia. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74:1570–7.

Yang M, Hagenauer J, Dijst M, Helbich M. Assessing the perceived changes in neighborhood physical and social environments and how they are associated with Chinese internal migrants’ mental health. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1240.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cheng M, Duan C. The changing trends of internal migration and urbanization in China: new evidence from the seventh National Population Census. China Popul Dev Stud. 2021;5:275–95.

Article Google Scholar

Ouyang W, Wang B, Tian L, Niu X. Spatial deprivation of urban public services in migrant enclaves under the context of a rapidly urbanizing China: an evaluation based on suburban Shanghai. Cities. 2017;60:436–45.

Article Google Scholar

Wang Z, Li Z, Cheng H. The equity of Urban Park Green Space accessibility in large Chinese cities: a case study of Wuhan City. Progress Geogr. 2022;41:621–35.

Article Google Scholar

Yang W, Yang R, Zhou S. The spatial heterogeneity of urban green space inequity from a perspective of the vulnerable: a case study of Guangzhou, China. Cities. 2022;130:103855.

Article Google Scholar

Wu J, He Q, Chen Y, Lin J, Wang S. Dismantling the fence for social justice? Evidence based on the inequity of urban green space accessibility in the central urban area of Beijing. Environ Plann B: Urban Analytics City Sci. 2020;47:626–44.

Google Scholar

Kjellstrom T, Mercado S. Towards action on social determinants for health equity in urban settings. Environ Urbanization. 2008;20:551–74.

Article Google Scholar

Cheng H, Su L, Li Z. How does the neighbourhood environment influence migrants’ subjective well-being in urban China? Population. Space Place. 2024;30:e2704.

Article Google Scholar

Arnberger A, Allex B, Eder R, Wanka A, Kolland F, Wiesböck L, et al. Changes in recreation use in response to urban heat differ between migrant and non-migrant green space users in Vienna, Austria. Volume 63. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening; 2021. p. 127193.

Dixon J, Tredoux C, Davies G, Huck J, Hocking B, Sturgeon B, et al. Parallel lives: Intergroup contact, threat, and the segregation of everyday activity spaces. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2020;118:457.

Article Google Scholar

Maas J, Van Dillen SM, Verheij RA, Groenewegen PP. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health Place. 2009;15:586–95.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gentin S, Pitkänen K, Chondromatidou AM, Præstholm S, Dolling A, Palsdottir AM. Nature-based integration of immigrants in Europe: a review. Volume 43. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening; 2019. p. 126379.

Wood L, Hooper P, Foster S, Bull F. Public green spaces and positive mental health – investigating the relationship between access, quantity and types of parks and mental wellbeing. Health Place. 2017;48:63–71.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mitchell R, Popham F. Greenspace, urbanity and health: relationships in England. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2007;61:681.

Article Google Scholar

Sugiyama T, Leslie E, Giles-Corti B, Owen N. Associations of neighbourhood greenness with physical and mental health: do walking, social coherence and local social interaction explain the relationships? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:e9.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Byrne J. When green is White: the cultural politics of race, nature and social exclusion in a Los Angeles urban national park. Geoforum. 2012;43:595–611.

Article Google Scholar

Wu L, Kim SK. Health outcomes of urban green space in China: evidence from Beijing. Sustainable Cities Soc. 2021;65:102604.

Article Google Scholar

Wolch JR, Byrne J, Newell JP. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: the challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc Urban Plann. 2014;125:234–44.

Article Google Scholar

Xiao Y, Wang Z, Li Z, Tang Z. An assessment of urban park access in Shanghai–implications for the social equity in urban China. Landsc Urban Plann. 2017;157:383–93.

Article Google Scholar

You H. Characterizing the inequalities in urban public green space provision in Shenzhen, China. Habitat Int. 2016;56:176–80.

Article Google Scholar

Gould K, Lewis T. Green gentrification: urban sustainability and the struggle for environmental justice. Routledge; 2016.

Du H, Song J, Li S. Peasants are peasants’: prejudice against displaced villagers in newly-built urban neighbourhoods in China. Urban Stud. 2021;58:1598–614.

Article Google Scholar

Xiao Y, Hui EC, Wen H. The housing market impacts of human activities in public spaces: the case of the square dancing. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 2020;54:126769.

Article Google Scholar

Harris B, Schmalz D, Larson L, Fernandez M. Fear of the unknown: examining Neighborhood Stigma’s Effect on Urban Greenway Use and surrounding communities. Urban Affairs Rev. 2021;57:1015–48.

Article Google Scholar

Hall SM. Migrant margins: the streetlife of discrimination. Sociol Rev. 2018;66:968–83.

Article Google Scholar

Tan Y. Temporary migrants and public space: a case study of Dongguan, China. J Ethnic Migration Stud. 2021;47:4688–704.

Article Google Scholar

Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health: final report of the commission on social determinants of health. World Health Organization; 2008.

Zhang N, Gereke J, Baldassarri D. Everyday discrimination in public spaces: a field experiment in the Milan Metro. Eur Sociol Rev. 2022;38:679–93.

Article Google Scholar

Maas J, Verheij RA, Groenewegen PP, de Vries S, Spreeuwenberg P. Green space, urbanity, and health: how strong is the relation? J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2006;60:587–92.

Article Google Scholar

Wolff M, Scheuer S, Haase D. Looking beyond boundaries: revisiting the rural-urban interface of Green Space accessibility in Europe. Ecol Ind. 2020;113:106245.

Article Google Scholar

Wu L, Kim SK, Lin C. Socioeconomic groups and their green spaces availability in urban areas of China: a distributional justice perspective. Environ Sci Policy. 2022;131:26–35.

Article Google Scholar

Neier T. The green divide: a spatial analysis of segregation-based environmental inequality in Vienna. Ecol Econ. 2023;213:107949.

Article Google Scholar

Freeman L. Displacement or succession? Residential mobility in gentrifying neighborhoods. Urban Affairs Rev. 2005;40:463–91.

Article Google Scholar

Chu E, Michael K. Recognition in urban climate justice: marginality and exclusion of migrants in Indian cities. Environ Urbanization. 2019;31:139–56.

Article Google Scholar

Corburn J, Riley L. Slum health: from the cell to the street. Univ of California; 2016.

National Bureau of Statistics. Major figures on 2020 Population Census of China (statistical yearbook). Beijing: China Statistics; 2021.

Google Scholar

Health Commission of Hubei Province. Report on Hubei’s migrant Population Development 2014–2017. Wuhan: Wuhan University; 2018.

Google Scholar

Ye S. Factor structure of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12): the role of wording effects. Pers Indiv Differ. 2009;46:197–201.

Article Google Scholar

Goldberg DP, Oldehinkel T, Ormel J. Why GHQ threshold varies from one place to another. Psychol Med. 1998;28:915–21.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Xie S. Quality matters: housing and the mental health of rural migrants in urban China. Hous Stud. 2019;34:1422–44.

Article Google Scholar

Wrede O, Löve J, Jonasson JM, Panneh M, Priebe G. Promoting mental health in migrants: a GHQ12-evaluation of a community health program in Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:262.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mooney SJ, Joshi S, Cerdá M, Kennedy GJ, Beard JR, Rundle AG. Neighborhood Disorder and physical activity among older adults: a longitudinal study. J Urban Health. 2017;94:30–42.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zhang Y, Wang J, Chen Y, Ye J. An assessment of urban parks distribution from multiple dimensions at the community level: a case study of Beijing. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2021;91:106663.

Article Google Scholar

Xing L, Liu Y, Liu X. Measuring spatial disparity in accessibility with a multi-mode method based on park green spaces classification in Wuhan, China. Appl Geogr. 2018;94:251–61.

Article Google Scholar

Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2:335–51.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hamilton LC. Statistics with Stata: version 12. Cengage Learning; 2012.

Rappaport LM, Amstadter AB, Neale MC. Model fit estimation for multilevel structural equation models. Struct Equation Modeling: Multidisciplinary J. 2020;27:318–29.

Article Google Scholar

Zhan D, Kwan M-P, Zhang W, Chen L, Dang Y. The impact of housing pressure on subjective well-being in urban China. Habitat Int. 2022;127:102639.

Article Google Scholar

Ji JS, Zhu A, Lv Y, Shi X. Interaction between residential greenness and air pollution mortality: analysis of the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4:e107–15.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Feng X, Astell-Burt T. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53:616–24.

Huang B, Yao Z, Pearce JR, Feng Z, Browne AJ, Pan Z, et al. Non-linear association between residential greenness and general health among old adults in China. Landsc Urban Plann. 2022;223:104406.

Article Google Scholar

Kimpton A, Corcoran J, Wickes R. Greenspace and Crime: an analysis of Greenspace types, neighboring composition, and the temporal dimensions of crime. J Res Crime Delinquency. 2017;54:303–37.

Article Google Scholar

Cai M, Jiao J, Luo M, Liu Y. Identifying transit deserts for low-income commuters in Wuhan Metropolitan Area, China. Transp Res Part D: Transp Environ. 2020;82:102292.

Article Google Scholar

Zhang L, Han R, Cao H. Spatiotemporal transformation of urban social landscape: a case study of Wuhan, China. Soc Indic Res. 2022;163:1037–61.

Article Google Scholar

Download references

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42301255 and 42171203) and the Key Laboratory of Ecology and Energy Saving Study of Dense Habitat, Ministry of Education in China (Grant No. 20221450059).

Department of Urban and Rural Planning, School of Architecture, Southwest Jiaotong University, No. 999, Xi’an Road, Pidu District, Chengdu, China

Hanbei Cheng

School of Urban Design, Wuhan University, No 8. Donghu Road, Wuhan, China

Zhigang Li, Feicui Gou, Zilin Wang & Wenya Zhai

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Hanbei Cheng: Writing–review & editing, original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. Zhigang Li: Writing–review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation. Feicui Gou: Writing–original draft, Visualization, Data Analysis, Software, Methodology. Zilin Wang: Visualization, Software, Methodology. Wenya Zhai: Visualization, Software, Methodology.

Correspondence to Hanbei Cheng or Feicui Gou.

The study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Wuhan University, where the first and corresponding authors were affiliated during the data collection period. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation. Participants were explained the study protocol and provided oral consent accordingly. They also received compensation upon completing the survey.

Not Applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

Cheng, H., Li, Z., Gou, F. et al. Urban green space, perceived everyday discrimination and mental health among rural-to-urban migrants: a multilevel analysis in Wuhan, China. BMC Public Health 24, 2788 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-20269-3

Download citation

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-20269-3

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Collection

Advertisement

ISSN: 1471-2458

By using this website, you agree to our Terms and Conditions, Your US state privacy rights, Privacy statement and Cookies policy. Your privacy choices/Manage cookies we use in the preference centre.

© 2024 BioMed Central Ltd unless otherwise stated. Part of Springer Nature.