In his first term, former President Donald Trump sought to significantly expand school choice, slash K-12 spending, and tear down the U.S. Department of Education, all while pouring fuel on the K-12 culture war fires.

Get ready for a reprise if Trump returns to the White House.

To be sure, much of Trump’s first-term K-12 agenda hit the skids. His administration’s most ambitious school choice proposal—a broad federal tax credit scholarship—never got traction. Congress largely rejected his proposed K-12 cuts. The education department is still around.

Still, the former president’s fans and critics alike say policies Trump promoted in his first term continue to resonate—and he might be more successful in notching K-12 wins the second time around.

“In the first term, I saw President Trump lay out an incredible vision and I saw Congress not move the way that they should have on his initiatives,” said Ryan Walters, Oklahoma’s GOP superintendent of public instruction and one of Trump’s loudest K-12 supporters. But now, “the president is more popular than ever. I think he’s going to come into office full steam ahead and get things done.”

“This is genuinely time to get nervous,” said Mary Kusler, the senior director for the Center for Advocacy and Political Action at the National Education Association, a 3-million-member union. “Unlike the last administration, where he was not expected to win and did not come in any way prepared for what it would be like to govern, they have told us exactly what they plan to do” in part through action in the first term.

Here’s a look at what Trump attempted on K-12 last time he was in power, how those proposals fared, and what might happen on K-12 policy if he reclaims the presidency.

FIRST-TERM ACTION

Though Trump—like many in the GOP going back to the Reagan era—campaigned on scrapping the department, he never actually proposed to do so once he was in the White House.

Instead, his administration proposed combining the departments of education and labor into a single agency focused on workforce readiness and career development. The idea made headlines for a few days, then disappeared into the political ether.

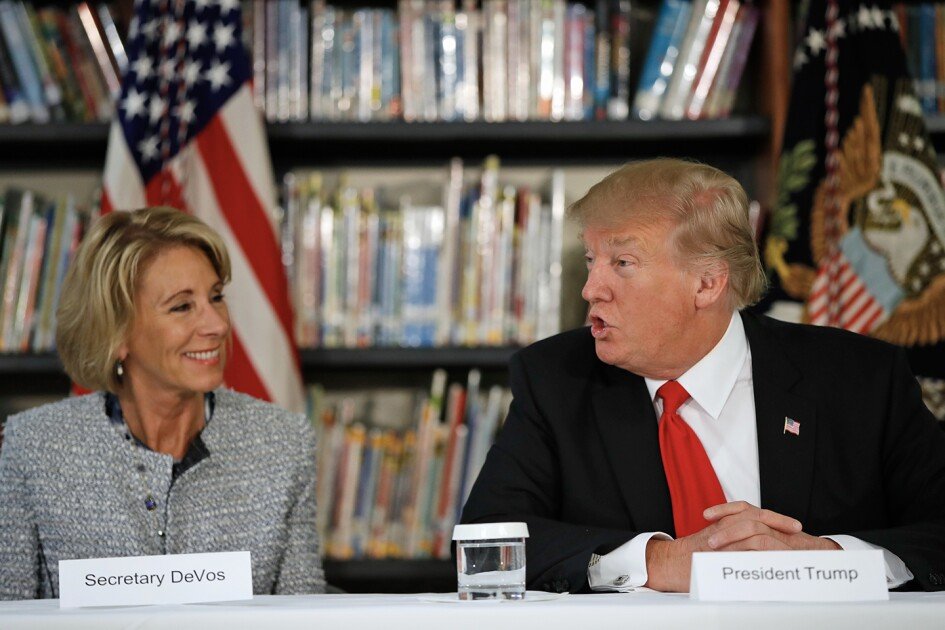

On a smaller scale, Trump’s education secretary, Betsy DeVos, consolidated offices within the Education Department.

And under Trump, staffing levels shrank significantly in the office of elementary and secondary education, which is charged with overseeing billions in funding for K-12 schools, most of it aimed at vulnerable children. The office lost nearly 14 percent of its staff between the end of the Obama administration in January 2017 and the midpoint of the Trump administration at the start of 2019. And morale was down throughout the department, a report by the Office of Personnel Management found.

Second-term potential

On the campaign trail, Trump has again proposed dismantling the education department. That’s a perennial GOP wish list item that has never gotten far in Congress—and seems unlikely to this time around.

Trump has never been specific about the fate of major federal programs districts depend on—such as Title I grants to help districts educate K-12 students from low-income families—if the department were dismantled. Some of Trump’s allies, such as Walters, have suggested that Title I and other funding streams could be block-granted to states.

Even though the department seems likely to survive another Trump term, the former president’s critics worry about the message a push to abolish it sends.

“When you talk about eliminating the Department of Education, you’re really talking about making it harder for our most vulnerable students to get the education they deserve,” Kusler said.

FIRST-TERM ACTION

In every budget request, Trump proposed deep cuts to the U.S. Department of Education’s bottom line, only to see them rejected by Congress. That dynamic played out even during the early years of his administration when both chambers were under GOP control.

For instance, in his first budget blueprint, released in March 2017, Trump sought to slash the Education Department’s then roughly $68 billion budget by $9 billion, or 13 percent, whacking popular programs that help districts offer after-school programs and hire and train teachers. Those programs stayed on Trump’s chopping block through his final budget request, which sought to cut the department’s bottom line by 10 percent.

Still, both programs—Supporting Effective Instruction State Grants, or Title II, currently funded at nearly $2.2 billion, and the 21st Century Community Learning Centers program, currently funded at more than $1.3 billion—are still on the books. So are the dozens more programs Trump sought to eliminate.

Perhaps ironically, Trump also presided over some of the biggest ever one-time cash infusions to K-12 school districts and state education agencies. They received more than $60 billion in federal pandemic relief as a result of legislation Trump signed.

Second-term potential

It seems likely that Trump will propose similar budget cuts again. Even if Congress spared programs on the chopping block—like it did in Trump’s first term—the uncertainty would hit at a terrible time for school districts, Kusler said.

Federal pandemic relief dollars are “expiring right now,” she said. “We know that school districts across America are scrambling to figure out how to keep school social workers, school psychologists, and others on the docket.”

What’s more, she said, many of the tax cuts that Trump enacted during his first term are set to expire at the end of next year. Extending them, as a second Trump administration would almost certainly push to do, could mean, “we’re about to go into a massive fight about whether or not we should be giving tax breaks to millionaires and billionaires instead of middle-class families,” Kusler said. “And the more we cut taxes, the less we have available to fund critical needs like education.”

On the other hand, Trump’s supporters argue that K-12 schools receive appropriate levels of federal aid—they’re just directing money to the wrong activities, such as social-and-emotional learning, instead of focusing on core academics like reading and math.

“We don’t have a funding problem, we have a priorities problem,” said Tiffany Justice, the co-founder of Moms for Liberty, a conservative grassroots advocacy organization.

FIRST-TERM ACTION

At the beginning of the Trump administration, long-time proponents of a federal school choice program thought their moment had finally come.

Trump spoke expansively about school choice on the campaign trail back in 2016, pitching a $20 billion school choice program that he said would be paid for using unspecified existing funds. He chose as his education secretary Betsy DeVos, the chairwoman of the American Federation for Children, a school choice research and advocacy organization.

But all that energy didn’t translate into much action, at least not at the federal level.

There was a behind-the-scenes push to include a federal tax credit scholarship in Trump’s marquee tax overhaul package. But the proposal, which would have offered federal tax credits nationwide for donors to organizations that award scholarships to support private school students, didn’t make it into the legislation.

Although the tax credit scholarship program was later introduced in 2019 as a standalone bill backed by the administration, it was never enacted. Other choice ideas—such as DeVos’ 2018 pitch to create education savings accounts for military-connected students that they could use to cover private education expenses—floundered on Capitol Hill.

Ultimately, the Trump administration notched one modest policy win on choice: A provision in the 2017 tax overhaul law that allowed families to use 529 college-savings accounts for K-12 private school tuition.

Second-term potential

Trump’s re-election could buoy a major school choice push already underway in states. Thanks in part to significant action over the past two years, 12 states have at least one private school choice that’s accessible to all K-12 students in the state or is on track to be, according to an Education Week analysis.

Meanwhile, just last month a U.S. House of Representatives committee approved legislation creating a federal tax credit scholarship. Though the bill would be unlikely to pass in the Democratic-controlled Senate this year, it could gain momentum if Trump wins and Republicans end up in control of Congress.

“We’ve done the groundwork so that in 2025 we have a realistic opportunity to get a bill,” on tax credit scholarships passed in Congress, said Jim Blew, who served in the Education Department during the Trump administration and is now a co-founder of the Defense of Freedom Institute, a nonprofit focused on conservative policy solutions. “We think if we got it on Trump’s desk, he would certainly sign it.”

A potential second Trump administration—like the first one—could also propose ESAs for some of the student groups over which the federal government has some authority, such as military-connected children.

And Trump’s education secretary could be a powerful force in convincing wavering states to pass sweeping school choice legislation, said Max Eden, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank.

“It’s easy to imagine [Trump’s new education team] trying to encourage the states that are on the fence but that could get across the finish line with universal ESAs, to pass them,” Eden said, naming Texas and Nebraska as possibilities.

FIRST-TERM ACTION

Trump’s administration spent its first few months in office undoing a spate of Obama administration initiatives aimed at helping marginalized groups of students.

Early in 2017, DeVos rescinded Obama’s Title IX guidance on the rights of transgender students. That directive required schools to allow students to use restrooms and locker rooms that match their gender identity, respond quickly to harassment of transgender students, let students use their gender identity on school forms and in assigning them to sex-segregated classes and activities, and keep students’ transgender status confidential, if they wished to keep it private.

Trump also supported an ultimately successful congressional effort to scrap Obama-era Every Student Succeeds Act guidance intended to strengthen the law’s requirements for ensuring states and districts focus on improving outcomes for disadvantaged students.

And in 2018, the Trump administration dumped Obama guidance aimed at ensuring schools don’t unfairly discipline students of color, who face suspensions and other consequences at rates higher than their peers.

What’s more, the department’s office for civil rights—a mighty power center in the Obama years—was lower-key during the Trump administration. It did little to promote the biannual civil rights data collection, saying that the data was self-reported by schools and therefore not meaningful, and even tossed some questions that civil rights advocates considered key.

The Obama team encouraged educators and advocates to file civil rights complaints. It got record numbers of significant resolutions in which school districts pledged to make changes on behalf of marginalized students.

Trump’s OCR office, by contrast, sought to move complaints along efficiently, Blew said.

“You could manage that [office] in a way that you streamline things, you get quick decisions on enforcement,” Blew said. “We said, ‘our job is to just figure out if there was a violation and then to enforce something around it.’”

Second-term potential

If Trump secures a second term, history will repeat itself on transgender student rights. His team will likely act quickly to rescind Biden’s Title IX regulation, which expands the scope of the law’s prohibition on sex discrimination so it also applies to discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

It also seems likely Trump would support the creation of a federal parents’ bill of rights. In March, the House passed legislation introduced by Rep. Hal Rogers, R-Ky., that would give parents access to the list of book titles in their children’s school libraries and require teachers to provide parents with their class curricula.

The legislation aims to empower groups like Justice’s Moms for Liberty, which have sought to keep books about race and gender identity out of schools. Proponents say it would bring much-needed transparency.

But others worry it could prevent schools from “teaching an honest view” of history, said Augustus Mays, the vice president for partnerships and engagement at the Education Trust, a nonprofit organization that advocates for students from low-income families and children of color.

But perhaps the Trump team’s most powerful lever in the culture wars could be OCR itself. In 2020, Trump’s Education Department started legal action against school districts in Connecticut that allowed students who were born male but identified as female to compete in girls’ track events.

It also initiated action against a Chicago-area school district that divided teachers into racially based “affinity groups” in order to have more open conversations during a professional development activity.

Though the Biden team dropped both cases, a Trump Education Department could go after school districts who pursue similar activities using Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits racial discrimination by programs that receive federal funding, Eden said.

That would “send a signal to K-12 school districts,” that some common diversity, equity, and inclusion practices, create “a hostile environment for teachers,” Eden said.

That rings alarm bells for Mays.

“Culturally responsive teaching has been attacked, at least at the state level, as being a divisive concept, even though we know having diverse educator workforce, having all teachers understand how to teach in a culturally responsive way, benefits all kids,” he said.

A second Trump administration would likely “amplify that at the federal level,” Mays continued. “That causes great concern for us.”